Mastering SOLID Principles: A Deep Dive with Real-World Analogies

The SOLID principles are the cornerstones of clean software architecture. Coined by Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob), these five design guidelines help developers build systems that are flexible, maintainable, and easy to scale.

Think of SOLID as a mindset — a way to future-proof your code by making it easier to adapt to change without breaking existing functionality.

🧩 1. Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

A class should have only one reason to change.

🧠 Why It Matters

When a class does too many things, it becomes difficult to maintain. A change in one part of its logic could unexpectedly break another. SRP promotes separation of concerns — each class should have one job.

💡 Real-World Example

Imagine you have a ReportGenerator that both creates and prints reports. If tomorrow you decide to change the printing format, you risk breaking report creation logic.

Bad Example:

class ReportGenerator {

generateReport(data: any) {

// logic to generate report

}

printReport(report: string) {

// logic to print report

}

}Better Design:

class ReportGenerator {

generateReport(data: any) {

// logic to generate report

}

}

class ReportPrinter {

print(report: string) {

// logic to print report

}

}Now, each class has one responsibility — generation and printing are decoupled.

🌍 Analogy

Think of SRP like a restaurant — the chef cooks, the waiter serves, and the cashier handles payments. If one person tried to do everything, mistakes would happen quickly.

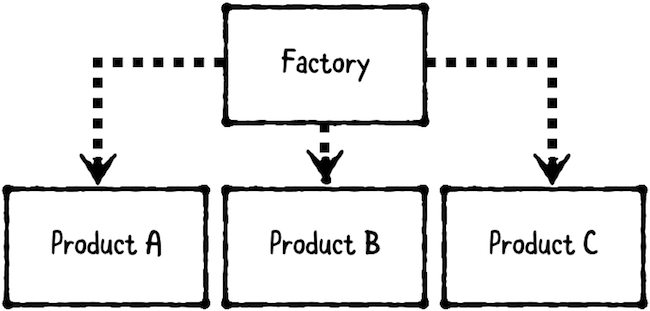

🧱 2. Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

Software entities should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

🧠 Why It Matters

You shouldn’t have to change existing code every time a new feature or variation is added. Instead, design your code so it can be extended with new functionality.

💡 Real-World Example

Let’s say you’re calculating invoices for different customer types.

Bad Example:

class InvoiceCalculator {

calculateTotal(type: string, amount: number) {

if (type === 'regular') return amount;

if (type === 'premium') return amount * 0.9;

}

}Adding a new customer type means editing the existing logic — risky and against OCP.

Better Design:

interface DiscountStrategy {

applyDiscount(amount: number): number;

}

class RegularCustomer implements DiscountStrategy {

applyDiscount(amount: number) { return amount; }

}

class PremiumCustomer implements DiscountStrategy {

applyDiscount(amount: number) { return amount * 0.9; }

}

class InvoiceCalculator {

constructor(private strategy: DiscountStrategy) {}

calculate(amount: number) { return this.strategy.applyDiscount(amount); }

}Now, you can easily add GoldCustomer without touching existing code.

🌍 Analogy

Think of a smartphone OS — you can install new apps (extend functionality) without modifying the OS core itself.

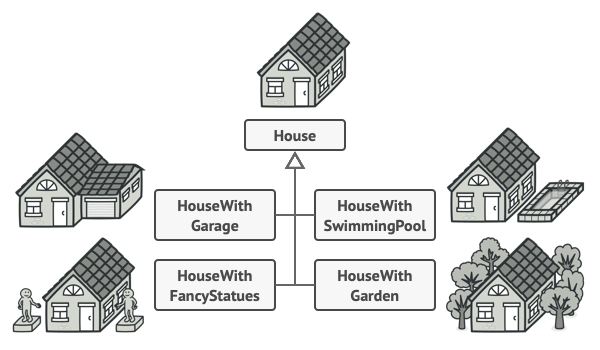

⚙️ 3. Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types.

🧠 Why It Matters

A subclass should behave in a way that doesn’t surprise or break expectations set by its parent class.

💡 Real-World Example

Bad Example:

class Bird {

fly() { console.log('Flying...'); }

}

class Penguin extends Bird {

fly() { throw new Error('Penguins can’t fly!'); }

}Using Penguin where a Bird is expected breaks functionality — it violates LSP.

Better Design:

class Bird {}

class FlyingBird extends Bird {

fly() { console.log('Flying...'); }

}

class Penguin extends Bird {

swim() { console.log('Swimming...'); }

}Each subclass now correctly represents its capabilities.

🌍 Analogy

If you borrow a car, you expect it to drive. If you get a boat instead, it might still be a vehicle, but it won’t behave as expected on the road.

🧮 4. Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

Clients should not be forced to depend on methods they do not use.

🧠 Why It Matters

Large, general-purpose interfaces lead to classes implementing unnecessary methods. Instead, split interfaces into smaller, focused ones.

💡 Real-World Example

Bad Example:

interface Worker {

work(): void;

eat(): void;

}

class Robot implements Worker {

work() { console.log('Robot working'); }

eat() { throw new Error('Robot doesn’t eat'); }

}The Robot class doesn’t need eat() but is forced to implement it.

Better Design:

interface Workable { work(): void; }

interface Eatable { eat(): void; }

class Human implements Workable, Eatable {

work() { console.log('Human working'); }

eat() { console.log('Human eating'); }

}

class Robot implements Workable {

work() { console.log('Robot working'); }

}Classes now depend only on the methods they need.

🌍 Analogy

You wouldn’t ask a robot waiter to taste food — only to serve it.

🧠 5. Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

🧠 Why It Matters

Coupling high-level logic directly to specific implementations makes code rigid. Abstractions act as contracts, allowing easy swapping of implementations.

💡 Real-World Example

Bad Example:

class MySQLDatabase {

connect() { console.log('Connected to MySQL'); }

}

class App {

db = new MySQLDatabase();

start() { this.db.connect(); }

}Switching to PostgreSQL would require modifying App — tightly coupled.

Better Design:

interface Database {

connect(): void;

}

class MySQLDatabase implements Database {

connect() { console.log('Connected to MySQL'); }

}

class PostgreSQLDatabase implements Database {

connect() { console.log('Connected to PostgreSQL'); }

}

class App {

constructor(private db: Database) {}

start() { this.db.connect(); }

}

const app = new App(new MySQLDatabase());

app.start();Now, App depends only on an abstraction — not the concrete database.

🌍 Analogy

A universal power adapter works with any plug type — that’s abstraction at work.

🎯 Wrapping It Up

| Principle | Core Idea | Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| S | One reason to change | Chef only cooks, doesn’t manage billing |

| O | Extend, don’t modify | Add apps to your phone, not rewrite the OS |

| L | Subclasses must behave like parents | Electric car still drives like a car |

| I | Keep interfaces focused | Don’t force a robot to eat |

| D | Depend on abstractions | Universal charger fits all plugs |

🚀 Final Thoughts

Following SOLID principles isn’t just about writing cleaner code — it’s about designing systems that can grow gracefully. These principles serve as a moral compass for developers, guiding you toward modular, testable, and adaptable architecture.

Build once, extend forever — that’s the power of SOLID.

Read more

System Design Question — Notification System (Factory) — Solution

Solution: Implement a Multi-Channel Notification System in TypeScript — problem statement, implementation, usage, and notes.

System Design Question — Configuration Manager (Singleton) — Solution

Solution: Implement a Singleton Configuration Manager in TypeScript — problem statement, implementation, usage, and notes.

System Design Question — Resume Builder (Builder) — Solution

Solution: Implement a Resume Builder in TypeScript — problem statement, implementation, usage, and notes.